Common menu bar links

History of Canada

The year 1608, Henry IV being on the throne of France and James I on that of England, may be regarded as the birth-year of Canada. The country and the name had been made known by the voyages of the Breton sea-captain, Jacques Cartier, of St. Malo, in the early half of the preceding century, and one or two ill-fated and wholly abortive attempts at settlement had subsequently been made; but in that year, under the leadership of Samuel de Champlain, of Brouages in Saintonge, a hold was taken of the soil that was not destined to be relaxed. It was but a slender colony that he planted under the shadow of the great rock of Quebec; but the germ of life was there, a life that for many years grew but feebly, that flickered at times as if on the point of extinction, but which, surviving all perils and difficulties, finally struck its roots deep and, gathering force, branched out into a numerous and vigorous people.

The claim of France to the St. Lawrence country was held to have been established by the discoveries made in the name of the French King, Francis I. It seems to have been assumed that what was then called Acadia, which may be described roughly as the region of our present Maritime provinces, had also become French territory, notwithstanding the fact that Cape Breton had been discovered in 1497 by John Cabot, sailing under a commission from Henry VII of England. During the five years preceding the arrival of Champlain's colony at Quebec, settlements had been attempted by the French at Port Royal (Annapolis) in Nova Scotia, and at the mouth of the St. Croix river, Champlain himself taking part in the expedition thither.

The main motive for the occupation of the country, so far as the individuals who took part in these enterprises—Champlain perhaps alone excepted—were concerned, was the command of the fur trade; though the royal commissions or patents under which they operated invariably contained stipulations for actual colonization and for missionary work among the Indians. These stipulations were more or less systematically evaded by a succession of associations or companies to whom privileges were granted. Of course there were difficulties in the way: the native Indians were very uncertain in their movements and dispositions, and at times were extremely menacing; but still the desire to colonize was not present. The feeling among the adventurers was that colonization would rather impede trade than promote it. Their vision was not one of happy homes for peaceful settlers; of a growing community requiring just laws and some sense of responsibility in their governors; but of trading stations from which all the world but themselves should be shut out. The public opinion which infallibly develops with population, even in backward states of society, was not desired; it never works well with monopoly.

Champlain's colony had at first consisted of about thirty persons. Twenty years later it barely exceeded one hundred, and then something happened. Charles I of England had made war on France and had sent an expedition to La Rochelle which met only with disaster. But amongst other things he had granted letters of marque to David Kirke authorizing him to attack the French possessions in Canada. Having fitted out a small fleet of privateers, Kirke's first stroke was to capture, early in 1628, in the mouth of the St. Lawrence, a French fleet of eighteen vessels, which were carrying out a number of new colonists for the settlement and badly needed supplies of provisions, goods, and military stores, which were being anxiously awaited at Quebec. It happened that just at this time Cardinal Richelieu, Louis the Thirteenth's great Minister, moved by the representations Champlain had made as to the miserable condition and prospects of the colony, and the little reliance that could be placed on any efforts which mere commercial speculators would make to develop the country, had determined to take the interests of the colony into his own special charge. The plan he had resolved upon was to create a company on a much wider basis than any previously formed, and consisting of persons of higher standing, acting under his own authority. Thus had come into existence the Company of New France, more generally known as the Company of the Hundred Associates. The preamble of the edict issued “set forth in forcible terms,” to quote a recent writer, “the lamentable failure of all previous trading associations to redeem their pledges in the matter of colonization; and the new associates were, by the terms of their charter, bound in the most formal and positive manner to convey annually to the colony, beginning in the year 1628, from two to three hundred bona fide settlers, and, in the fifteen following years, to transport thither a total of not less than four thousand persons male and female.” The charter contained other useful stipulations, including one for the maintenance of a sufficient number of clergy to meet the spiritual wants both of settlers and natives. Fulfilling these conditions, they were to have absolute sovereignty, under the French King, of all French possessions between Florida and the Arctic regions, and from Newfoundland as far west as they could take possession of the country.

It was in furtherance of these plans that the fleet was sent out which Kirke captured. Had Kirke chosen to sail up the St. Lawrence at once with a couple of well-appointed vessels, Quebec would in all probability have fallen to the English in the summer of 1628; but Kirke did not want to have a struggle if it could be avoided, and, shrewdly calculating that lack of provisions would in the course of a few months reduce the garrison to dire extremities, he postponed action till the following year. Things fell out as he expected and when he appeared before Quebec in July, 1629, Champlain had no choice but to capitulate, and for some three years the English, under a brother of Kirke's, were in possession of the place, Champlain with most of the French residents having returned to France.

On the 21st of July, 1629, the English flag was raised on Champlain's “habitation”; but, previously to this as it happened, peace had been signed between France and England, and all Kirke's work was undone. Canada was restored to France by the terms of the treaty of peace, and was formally handed over in the summer of 1632.

It now remained to be seen what Richelieu's company would effect. In truth it did not effect much, though a good beginning seemed to be made when Champlain returned to Quebec in May, 1633, bringing with him over a hundred intending settlers. His useful life was, however, drawing to a close, and on Christmas Day, 1635, he died in the sixty-ninth year of his age.

One or two special events of importance must be noted. In 1639 two ladies of distinction arrived from France to engage in educational and charitable work. These were Madame de la Peltrie and Madame Guyard, the latter better known as Mere de l'lncarnation. Their monument is the Ursuline Convent of Quebec, at which so many generations of girls, French Canadian and other, have been educated. In 1641 M. de Maisonneuve conducted a band of earnest followers to Montreal in order to found there a strictly Christian colony. Twelve years later Sister Margaret Bourgeoys established at Montreal the Congregation de Notre Dame for the education of girls, an institution that has gained a continental fame. The year 1668 is glorious in Canadian annals as the year of what has been called the Canadian Thermopylae, when, to avert an attack by a large force of Iroquois on Montreal, Dollard, a young inhabitant of the place, and a score or so of companions, threw themselves in their path, and so sternly and heroically defended a position they had fortified on the river Ottawa as to discourage the savage host and cause them to retrace their steps. Of the Canadians, all but one perished.

The year 1659 (just one hundred years before the “Conquest”) is marked by the arrival of Monseigneur de Laval, with the title of Bishop of Petraea, in partibus, and the powers of Vicar Apostolic, to preside over the church in New France: fifteen years had to elapse before he received full powers as Bishop of Quebec. In February, 1663, the most violent earthquake of which there is historical record in Canada occurred. The population were terror-stricken; but the damage done to property was slight and no lives were lost, nor do we read of bodily injuries sustained. In the same year it was that the Company of New France practically acknowledged their insolvency and made a surrender of all their rights and privileges to the King. They had not carried out their engagements; in fact they differed little from the less distinguished companies that had preceded them in making the interests of trade paramount. They had bound themselves, as we have seen, to plant in Canada not less than four thousand settlers in fifteen years, yet a census taken in 1666, thirty-five years after they had begun operations, showed that the whole population of the country fell short of three thousand five hundred.

The King accepted the surrender made by the Company, and following the example of Richelieu, who thought that a larger company might achieve success where a smaller one had failed, proceeded to establish a still larger one under the name of the West India Company. Colbert, the great Minister of Marine and Colonies and the incarnation of what has been called the mercantile system, was the inspirer of the idea; yet, as the prestige of Richelieu had not saved the Company of New France from shipwreck, neither did that of Colbert and his royal master combined save the Company of the West Indies.

The first governor of New France who has made a name for himself in history is Louis de Buade, Count Frontenac, who arrived in Canada in the year 1672; but a few years earlier a man on the whole of greater note had been sent to Canada as Intendant, an office involving financial and judicial authority exercised in nominal subordination to the Governor as the King's personal representative, but with a large measure of practical independence. This was Jean Talon. He appears to have been the first to perceive the industrial and commercial possibilities of the country, as he certainly was the first to take any effectual steps for their development. Mines, fisheries, agriculture, the lumber trade and one or more lines of manufacture all received his attention. He returned to France very shortly after the arrival of Frontenac, but he had given an impulse to the economic life of the country which had more or less lasting effects.

Frontenac, who was a veteran soldier, established good relations with the Iroquois, who had been the most dangerous enemies of the colony, and exercised a vigorous control generally, but his relations with the Intendant, Jacques Duchesneau, who succeeded Talon after an interval of three years, were most inharmonious, and with Bishop Laval not too friendly. So much trouble did the disputes which thus arose cause to the Home Government that he and the Intendant were both recalled in 1682. Two not very efficient governors, M. de la Barre, and the Marquis de Denonville, succeeded; the first served a term of three and the latter of four years, and then Frontenac, now in his seventieth year, was again sent out. It was on the day of his departure from France, August 5, 1689, that the terrible massacre by the Iroquois, narrated in all Canadian histories, occurred at Lachine.

A month or so before this, France had declared war on England as a sequel to the dethronement in the latter country of James II and the accession of William of Orange, and Frontenac made it his first duty on arriving in Canada to organize attacks on the neighbouring English colonies. The massacre at Lachine was outdone by a massacre by French and Indians at Schenectady, and two or three other raids of similar character were successfully carried out. Frontenac counted on the effect which these movements against the English would have on the minds of the Iroquois enemies of the colony, and they certainly tended to impress the natives with a sense of his power. Nevertheless when he sent envoys to those savages they were treated with great severity, two being burned and one soundly beaten and then handed over to the English as a prisoner.

The English colonists were not disposed to remain passive under these attacks. In May, 1690, an expedition under the command of Sir William Phipps, a native of what is now the state of Maine, who, for certain naval services, had earned a knighthood from King James II, sailed from Nova Scotia, and took possession of Port Royal and other forts and settlements in that region. With a greatly increased force, some thirty-two ships in all and over two thousand men, he set sail for Quebec in full expectation of capturing that fortress and making an end of French power in North America. The expedition proved a disastrous failure and involved the people of Boston in a very heavy financial loss. The opinion of Bishop Laval nevertheless was that if the fleet, which was greatly detained by contrary winds in its passage up the St. Lawrence, had arrived only a week earlier Quebec would have fallen.

The remaining years of Frontenac's second administration were marked by border warfare and negotiations with Indian allies and enemies. There were no serious attacks by the Iroquois in the colony in his time. In fact he established a general peace which was solemnly ratified a few years later. On the 28th November, 1698, he died.

During the remainder of the French regime the history of Canada was not marked by any very important events. The war of the Spanish Succession, into which England was drawn, caused a renewal of war on the Canadian frontier, two of the principal incidents being the massacres of English colonists at Deerfield and Haverhill in Massachusetts (1708). In the summer of 1711 a powerful expedition was despatched against Quebec by way of the St. Lawrence under the command of Sir Hovenden Walker. Had this force reached Quebec it was amply sufficient to overpower any opposition that could have been made to it, but the elements seemed to be arrayed against the invader. A number of transports, crowded with troops, were wrecked at Sept Îles, and the enterprise had to be abandoned. The war in Europe was, however, disastrous to France, and the Treaty of Utrecht (1714) transferred to England the French possessions of Acadia and Newfoundland. The limits of Acadia were not at the time defined with any accuracy, and the French continued to occupy the mouth of the St. John river and what is now the city of St. John. Cape Breton, or as they called it, Île Royale, was left by the treaty in their possession, together with Île St. Jean, now Prince Edward Island, and they perceived the importance of placing the former island at least in an adequate state of defence. Special attention was paid to the fortification of Louisburg. War having again broken out between England and France, an expedition was formed in New England under the command of Sir William Pepperell, to attack the French fortress. A small English squadron joined the expedition, and the capture of the place was accomplished on the 16th June, 1745. The peace of Aix la Chapelle, in 1748, restored the fortress and the whole island to France, to the great disappointment of the New Englanders. Ten years later (July 26th, 1758), the Seven Years' War having broken out, it again passed into the possession of Great Britain after a siege in which General Wolfe, who was to win still brighter laurels in the year following by the taking of Quebec, greatly distinguished himself.

The expedition against Quebec was part of the war policy of the great William Pitt, Earl of Chatham, and he it was who designated Wolfe for the command. The story of how Wolfe's army scaled the heights above the city on the night of September 12-13, 1759, is among the best known of historical incidents. The battle that ensued on the morning of the 13th has been rightly looked upon as one of the most decisive events in the world's history. Wolfe died in the arms of victory; Montcalm, no less gallant a soldier, was carried from the field fatally wounded, and expired on the following day. Quebec surrendered to the British, and the capitulation of Montreal, a year later, placed the whole country in their possession, though the Treaty of Paris by which Canada was ceded to Great Britain was not signed till February 10, 1763.

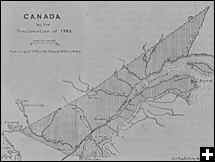

The conquest of Canada relieved the British colonies to the south from the apprehensions, under which they had laboured for nearly a hundred years, of attack from that quarter; and they soon began to be restive under the slight control exercised over them by the Mother Country,—a control limited almost exclusively to their overseas trade and compensated in no small measure by important privileges in the British markets. For a period of fifteen years after the conquest the Government of Canada was of a military type, and no small amount of confusion existed in the administration of justice and the general application of law to the affairs of the community. In the year 1774 an important step was taken in the passing of the Quebec Act, which established a council with limited legislative powers, sanctioned the use of French law in civil matters, confirmed the religious orders in the possession of their estates, granted full freedom for the exercise of the Roman Catholic religion and authorized the collection of the customary tithes by the clergy from their parishioners. The Act also defined the limits of Canada as extending as far south as the Ohio and as far west as the Mississippi. On that account, and also on account of the recognition granted to the Roman Catholic Church, it gave great umbrage to the older colonies. The year following witnessed the first bloodshed in their quarrel with the Mother Country (battle of Lexington).

Towards the end of that year, 1775, two bodies of colonial troops marched against Canada, one under Montgomery by way of Lake Champlain, and the other under Benedict Arnold through the woods of Maine. Montreal was captured and the two commanders joined forces some miles above Quebec. On the 31st of December each led an attack on that city from different quarters. Both attacks were repulsed; Montgomery was slain and Arnold was wounded. The Americans remained encamped to the west of the city during the winter without accomplishing anything; in the spring they retreated and shortly afterwards evacuated the country.

The task which devolved on Great Britain in the government of her new possession was one demanding an amount of practical wisdom which few of her statesmen possessed. The military men at the head of affairs in the colony—Murray, Carleton, Haldimand—were men of character and intelligence; but the questions arising between the two races, which found themselves face to face in Canada, as an English immigration began to flow into the country, both from the British Isles and from the colonies to the south, hardly admitted of theoretical treatment. In such matters experience and necessity have the decisive voice. The Quebec Act, which created a nominative Council but not a representative Assembly, did not satisfy the new-comers. Racial antagonism was at the time causing friction, and after mature consideration and hearing the representatives of different parties in the colony, the British Government decided on dividing the Province of Quebec into the two provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, and on giving to each a Legislature consisting of two Houses—a nominated Council and an elective Assembly. The population of Lower Canada at this time was about 165,000 and that of Upper Canada not less probably than 15,000. The population of the country as a whole had been greatly increased by the Loyalist emigration, partly voluntary partly compulsory, from the United States. In Lower Canada the exiles found homes chiefly in that portion of the province known as the Eastern Townships and in the Gaspé peninsula; and in Upper Canada in the townships fronting on the St. Lawrence river around the Bay of Quinté, in the Niagara district, and along the Detroit river. This element in the population would naturally be of a somewhat conservative cast, but not a few came shortly afterwards whose sentiments were of a more republican character.

It was not, however, only the Canadian provinces that received accessions to population from this source. Considerable bodies of Loyalists directed their steps to the provinces of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, and some also to Prince Edward Island. Wherever they chose to settle lands were granted to them by the British Government, and after a period of struggle with new conditions many began to find comfort and prosperity under the flag of their forefathers. These provinces all possessed, it should be remarked, what has been called a “pre-loyalist” element in their population, consisting of settlers from New England and other parts of what subsequently became the United States. These, as difficulties developed between Great Britain and her American colonies, did not, as a rule, manifest any very strong British feeling; and the relations between them and the later Loyalist settlers were not altogether cordial.

Nova Scotia, which had been British since its cession under the Treaty of Utrecht, received parliamentary institutions as early as 1758, though in practice the administration was mainly in the hands of the Governor of the province and his Council. Up to the year 1784 it was held to embrace what is now New Brunswick and also Cape Breton, but in that year these were both constituted separate provinces. Cape Breton was, however, reunited to Nova Scotia in the year 1820, not without considerable opposition on the part of the inhabitants.

The parliamentary institutions conferred upon the two Canada’s by the Act of 1791 did not a little to quicken political life in both provinces and also to stimulate immigration from the United States, which, there is reason to believe, had been in a measure retarded by a knowledge of the somewhat restricted political conditions prevailing in Canada up to that period. After a time a demand began to be made in both provinces, but less distinctly in the lower than in the upper, for what was designated as “responsible government.” Although both were increasing steadily in wealth and population there was a lack of vigorous impulsion in matters dependent on administrative and legislative action.

In the absence of the party system taxation was excessively unpopular, and without adequate appropriations public works could not be undertaken on the scale which the public interest required. In Upper Canada antagonism grew up between the official party, to which the name of the “Family Compact” was given, and those who desired more liberal institutions. In Lower Canada a similar condition of things was developed, but was complicated and embittered to an unfortunate extent by race feeling. The intentions of the Home Government were good, but the wants of the provinces were only imperfectly known, and the military governors who were sent out were, as a rule, not fitted to grapple with difficult political situations. In both provinces the Government had at its disposal certain revenues collected under an Imperial Customs Act passed as early as the year 1774 for the express purpose of providing a permanent means for carrying on the civil government. In both provinces the liberal party demanded that the revenue in question should be placed under the control of the local legislature. In Upper Canada the matter was amicably arranged, the legislature taking over the revenue and in return making a moderate permanent provision for the most necessary items of expense under the head of civil administration. In Lower Canada the legislature took over the revenue as offered by the Home Government, but refused to make any such provision. Several years of political conflict ensued, the legislature refusing supplies and the Government being obliged to take money from the military chest in order to pay salaries to the public officers. Finally an Imperial Act was passed (February 10, 1837) suspending the constitution of Lower Canada and authorizing the application of the provincial funds to necessary purposes.

In following the course of the internal political development of the country the present narrative has been carried past a very serious crisis in its earlier history, the war of 1812-15,—a war which is now looked back to across the space of a century as the last occasion on which Great Britain and the United States confronted one another in arms. The causes of the conflict have no connection with Canadian history, as they related entirely to the commercial and naval policy of Great Britain under stress of a deadly and exhausting struggle with Napoleon Bonaparte, then at the acme of his military power. Canada was, however, at once made the theatre of operations, and Canadian loyalty to the Mother Country was put to a test to which it nobly responded. The beginning of the war was signalized by the brilliant success of General Brock, who, in the absence of the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, Mr. Gore, was both the military and the civil chief of the province, in capturing Detroit, held by an American force much superior to his own (August 16, 1812), and by the battle of Queenston Heights (October 13, 1812), in which an invading force was driven back with heavy loss in killed, wounded and prisoners, but in which the gallant Brock fell a victim to his own too reckless bravery. The subsequent course of the struggle was marked on both sides by alternate victory and defeat. In two naval battles, Lake Erie (September 10, 1813) and Lake Champlain (September 11, 1814), the British fleets sustained serious reverses; while in the engagements of Stoney Creek (June 5, 1813) and Chrysler's Farm (November 11, 1813) and the very decisive one of Chateauguay (October 26, 1813) victory rested with the defenders of the soil of Canada. The main effect of the war, which was brought to a close by the Treaty of Ghent (December 24, 1814), was to strengthen British sentiment in Canada and to give to the Canadians of both provinces an increased sense both of self-reliance and of confidence in the protection of the Mother Country in any hour of need.

Lower Canada suffered but little from the depredations of the enemy. Upper Canada on the other hand suffered seriously, her capital, York, having been captured and its public buildings burnt (April, 1813) and a large extent of her frontier devastated. Nevertheless when Mr. Gore returned to the province in September, 1815, he reported that the country was in a fairly prosperous condition, somewhat more so than before the war, owing to the large amount of ready money which the necessary expenditure had put into circulation.

Towards the close of the year 1837, to resume the domestic history of the country, the political disagreements to which reference has been made resulted in attempts at armed rebellion in both the Canadian provinces, attempts that were speedily repressed, especially that in Upper Canada, which was confined to a comparatively small section of the population, and which occurred at a moment when the Provincial Government, under Sir F. B. Head, was supported by a large majority of the legislative body.

In consequence of these troubles the Home Government decided to send out a special commissioner, charged with the duty of making a thorough investigation, not only of the Canadian situation, but of the general condition of all the North American provinces,—as all had in a greater or less degree been suffering from political restlessness,—in order to see if it were not possible to allay irritation, and by certain judicious changes to place things in all the provinces on a satisfactory working basis. The person chosen was the Earl of Durham, son-in-law of the second Earl Grey, a man of marked ability and of advanced liberal views.

His Lordship arrived at Quebec on the 29th of May, 1838, commissioned as Governor General of the whole of British North America. His stay in the country only lasted five months, but he was nevertheless able to lay before the British Government in the month of January, 1839, an exhaustive report, dealing principally with the affairs of the Canadas. He recognized, as might have been expected, that the time had come for granting a larger measure of political independence to both provinces, and, without indicating the scope he was prepared to allow to the principle, made it clear that in his opinion the chief remedy to be applied was “responsible government.” This however was to be conditional on a reunion of the provinces as a means of balancing the two races into which Canada was divided, and procuring as far as might be possible their harmonious co-operation in working out the destinies of the country. The imperial authorities approved the suggestion, which, however, they recognized as involving very considerable difficulty. Lord Durham might perhaps have been entrusted with the duty of carrying it into effect had he not very summarily thrown up his commission on account of the criticism which a particular measure of his had encountered in the British Parliament, and from which in his opinion the Government had not shielded him as it should have done. The man who in these circumstances was designated for the task was Charles Poulett Thomson, afterwards raised to the peerage as Baron Sydenham and Toronto.

Thomson arrived at Quebec in October, 1839, and applied himself with great vigour to his task, the most difficult part of which was to render the proposition acceptable to the province of Upper Canada, then in full possession of its constitutional rights. The constitution of Lower Canada, as already mentioned, had been suspended, and had been replaced by the appointment of a Special Council with limited powers. After much strenuous negotiation Thomson succeeded in abating certain excessive demands of the western province, and, as the Special Council in Lower Canada was favourable to the scheme, he was able to draft a Bill which with a few modifications the Home Government adopted and put through Parliament (1840). General elections were held in February, 1841, and the legislature of the united provinces met in June of that year. On the 3rd of September Mr. Robert Baldwin, then representing the constituency of North York, proposed certain resolutions affirming the principle of responsible government, which were carried with little or no opposition. On the following day Lord Sydenham (he had received this title some weeks before) met with an accident while riding which proved fatal. He died on the 19th September, 1841.

The French Canadians were almost without exception opposed to the union, and it was therefore impossible at the time to obtain cooperation of any of their leading men in the formation of a ministry. Sir Charles Bagot, Lord Sydenham's successor, fully recognized, as indeed Lord Sydenham himself had done, that the situation was a most unsatisfactory one; moreover he saw how easily a combination might at any moment be formed with the French Canadian vote in the Assembly to defeat his Government. He saw indeed such a combination on the point of being formed, and he resolved to ask Mr. Lafontaine, the most influential French Canadian in the House, whether he could not consent to take Cabinet office. On condition that Mr. Baldwin should be taken in at the same time and one or two other changes made in the Cabinet, that statesman was prepared to accept the proposal, and the matter was arranged accordingly. The Government so formed may be regarded as the first Canadian Ministry in the usual acceptation of the word.

Sir Charles Bagot died at Kingston in the spring of 1843, after a long and distressing illness. His successor, Sir Charles Metcalfe, had a misunderstanding with his Ministers on a question of patronage. With one exception they resigned. A general election followed, with the result that the Governor General was overwhelmingly sustained in Upper Canada, while Lower Canada gave an almost equal majority in favour of the late Government. The Draper-Viger Government which now came into power, had a most precarious support in the Assembly, and in the general election of January, 1848, Lord Elgin being Governor-General at the time, Baldwin and Lafontaine were restored to office by a large majority. A leading member of their Government was Mr. (afterwards Sir) Francis Hincks, who occupied the post of Inspector General, or, as he would to-day be designated Finance Minister. Baldwin and Lafontaine having both retired in 1851 the Government was reconstructed, with Mr. Hincks as Prime Minister and Mr. A. N. Morin as leader of the Lower Canada section.

Much useful legislation must be credited to the Baldwin-Lafontaine Ministry. The session of 1849 alone produced: the Judicature Act; the Municipal Corporations Act, which gave Canada a workable system of local government substantially the same as that which exists to-day; the Act for amending the charter of Toronto University and greatly enlarging the basis of that institution; an Amnesty Act, which enabled any hitherto unpardoned rebels of 1837-8 to return to the country; and the Rebellion Losses Act. The latter Act, though carefully framed to exclude any payments to persons who had actively participated in the rebellion, was represented by certain opponents of the Government as designed to recompense such persons; and its signature by Lord Elgin was followed by rioting in Montreal, then the seat of Government. The Governor General was mobbed as he drove through the streets, and early in the evening the legislative buildings were set on fire and totally destroyed (April 25, 1849). One result was the removal of the seat of government to Toronto in the fall of the same year and the adoption of a system by which that city and Quebec were to be the seat of government alternately. The Ministry of Mr. Hincks was chiefly remarkable for the steps taken to develop a railway system in Canada and for the adoption of a Reciprocity Treaty between Canada and the United States. In the arrangement of this treaty Lord Elgin took the deepest interest, and it was due in a large measure to his skilful diplomacy and unusual powers of persuasion that the negotiations proved successful. Mr. Hincks himself visited Washington and argued the case very strongly in papers submitted to Congress. The treaty was undoubtedly beneficial to Canada, particularly when the outbreak of the War of Secession (1861) caused a greatly increased demand for farm products of every kind.

Although it cannot be doubted that the union of the provinces, together with the introduction of responsible government, by enlarging the political and social life of Canada, gave a stimulus to all the activities of the country, grave political difficulties were nevertheless not long in developing. The differences between the eastern and western sections of the province were very marked, and any political party which rested mainly on the votes of either province was sure to incur keen opposition in the other. The Draper-Viger Government, formed by Sir Charles Metcalfe, rested mainly on Upper Canada votes; the Baldwin-Lafontaine Government, which followed, rested mainly on Lower Canada votes. The Act of Union had given equal representation in the Assembly—forty-two members—to each section of the province. Lower Canada at the time had the larger population; but many years had not elapsed before, mainly through immigration, the balance was in favour of Upper Canada. An agitation then sprang up in the west for representation by population, but the demand was stoutly resisted by Lower Canada. The Hincks Government was defeated in 1854 by a combination of Conservatives and Reformers, and was succeeded in September of that year by a coalition under the premiership of Sir Allan MacNab. Under the new Government two very important measures were carried: the secularisation of the clergy reserves, which for over twenty years had been a subject of serious contention in the country, and the abolition of what was known in Lower Canada as the seigniorial tenure. Both were progressive measures, and the first was as strongly approved in Upper Canada as the second in Lower Canada.

In 1855 the seat of government, which had been removed from Toronto to Quebec in the fall of 1851, was again transferred to the former city, where it remained till the summer of 1859. It was during this period that the question of a permanent seat of government was decided in favour of Ottawa by Her Majesty Queen Victoria, to whom it had been left by a vote of the Canadian Parliament. Considerable progress was meanwhile being made in the material development of the country. Even before the union some important steps had been taken towards the development of a canal system. The Lachine canal was opened for traffic in 1825; the Welland canal in 1829; the Rideau Canal, constructed entirely at the expense of the Home Government, in 1832; and the Burlington canal, which made Hamilton a lake port, in the same year. An appropriation was made by the Upper Canada Legislature in 1832 for the Cornwall canal, but various causes, including the rebellion, interfered with the progress of the work, and it was not till the end of the year 1842 that it was completed. Further developments and improvements of the canal system followed, and the progress in this respect has been continuous to the present day. The total expenditure on canals in Canada down to the date of Confederation has been estimated at over $20,500,000.

The first steam railway in Canada was one between Laprairie, at the foot of the Lachine rapids on the south shore of the St. Lawrence, and St. Johns, on the Richelieu River, supplying a link in the railway and water communication between Montreal and New York. The date of its opening was 1837. Two years later a railway was opened between Queenstown and Chippawa, giving communication around the rapids and falls of the Niagara River. In 1847 a line was opened between Montreal and Lachine. The 'fifties were however pre-eminently the period of railway expansion in pre-Confederation times. In 1853 and 1854 the Great Western Railway was opened from Niagara Falls to Hamilton, London and Windsor. In 1853 communication was completed between Montreal and Island Pond, establishing connection with a line from that place to Portland, and in 1854 the line was opened between Quebec and Richmond, thus giving railway communication between Quebec and Montreal. In December, 1855, communication was established between Hamilton and Toronto, in 1856 by the Grand Trunk railway between Montreal and Toronto. The Northern railway from Toronto to Collingwood was completed in 1855 and the Buffalo and Lake Huron railway between Fort Erie and Goderich in 1858, though sections of it had been completed and operated earlier.

River and Lake navigation was very steadily developed from the year 1809 when a steamer named Accommodation, owned by Mr. John Molson of Montreal, began to ply between Montreal and Quebec. The year 1816 saw the Frontenac launched in Lake Ontario. Year by year larger and faster vessels were placed on our inland waters, the chief promoters of steamboat enterprises being in Upper Canada the Hon. John Hamilton of Kingston and in Lower Canada the Hon. John Molson. A large and powerful steamboat interest had been created in the middle 'fifties, when the competition of the Grand Trunk railway, of which section after section was being opened, gave a serious blow to lake and river transportation.

It was in the 'fifties also that steam navigation was established between Canada and Great Britain. Mr. (afterwards Sir) Hugh Allan, of Montreal, was the pioneer in this important enterprise. As early as 1853 some vessels of about 1,200 tons capacity were placed upon the route between Montreal and Liverpool, and in 1855 a mail contract was assigned to the Allan firm for a fortnightly service, which took effect in the year following. The early history of this enterprise was marked by an unparalleled and most discouraging series of disasters; but with unflagging courage the owners of the Allan Line held to their task, repaired their losses as best they could, and gradually succeeded in giving the service a high character for regularity and safety.

In 1856 Mr. (afterwards Sir) John A. Macdonald, who as Attorney General for the West, had been perhaps the man to exercise the greatest influence in the Coalition Government, succeeded to the premiership, ill-health having compelled the retirement of Sir Allan MacNab. Party spirit from this time onwards ran very high. Although a certain section of the Reformers had supported the Coalition Government the bulk of the party remained in opposition under the leadership of George Brown, whose policy, while it won him many adherents in western Canada, had an opposite effect in Lower Canada, and thus tended to bring the two sections of the province more or less into antagonism.

The idea of a federation of the British provinces in North America had been mooted at various times in the previous history of the provinces. It had been hinted at in the discussion in the House of Commons on the Constitutional or Canada Act in 1791. William Lyon Mackenzie suggested it in 1825, and Lord Durham had given it his consideration, but was led to believe it was impracticable at the time. The idea was taken up and strongly advocated by the British American League, a short-lived political organization of a Conservative character formed at Montreal in 1849, with branches in other cities. In 1851 the question was brought before the Legislature, but a motion for an address to the Queen on the subject only secured seven votes. In 1858 however a strong speech in its favour was made by Mr. (afterwards Sir) A. T. Galt. In the summer of that year the Government led by Mr. J. A. Macdonald was defeated on the seat of government question, but resumed power after a two days' interval, during which Mr. Brown had formed a Government, but had immediately resigned on being refused a dissolution of Parliament by the Governor, Sir Edmund Head. In the Government as reconstructed Mr. Cartier replaced Mr. Macdonald as premier, while Mr. Galt, who had not previously held office, became Inspector General, the understanding being that the policy of the Government would embrace the advocacy and promotion of a union of the colonies. The political situation in Great Britain however was not favourable to any decisive action at the time, and some years elapsed before the question was taken up in a practical manner.

Towards the close of the year 1861 the country had been greatly excited over the Trent difficulty with the United States. At one moment war between Great Britain and the Republic seemed imminent. It was doubtless under the influence of the national feeling, not to say the apprehensions, thus aroused, that the Government led by Mr. Cartier introduced a Militia Bill of very wide scope. The Government at this time was receiving an extremely precarious support; and on their Militia Bill they sustained a decisive defeat, largely owing to the unpopularity of the measure in Lower Canada. Upon the resignation of Mr. Cartier and his colleagues Mr. J. S. Macdonald was entrusted with the task of forming a Government. Two short-lived Administrations followed, when it became apparent that parliamentary government in Canada as then constituted had come to a dead stop. On several fundamental questions there was an antagonism of views between Eastern and Western Canada which made it impossible for any Government that could be formed to receive adequate support. Then it was that the idea of a larger union, with a relaxation of the bonds in which Upper and Lower Canada were struggling, forced itself on the attention of the leading men of both parties. The leader in this new path was undoubtedly Mr. George Brown, who early in the session had been appointed chairman of a committee to consider the best means of remedying the political difficulties referred to. The committee had expressed themselves as in favour of a federative system, either as between Upper and Lower Canada or as between all the British North American colonies. Mr. Brown having consented to co-operate, if necessary, with his political opponents to that end, a Coalition Government was formed under the leadership of Mr. J. A. Macdonald, Mr. Brown accepting the position of President of the Council.

At this very time the three Maritime provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island were considering the question of a federal union amongst themselves, and had arranged a meeting at Charlottetown in September to consider the matter. Thither a delegation from the legislature of Canada repaired to invite the attention of the Maritime delegates to a larger scheme. It was agreed to adjourn the Convention to Quebec, there to meet on the 10th October. From the deliberations which then took place sprang the Dominion of Canada as it exists to-day; for although the federation as formed by the British North America Act only embraced the provinces of Ontario and Quebec (Upper and Lower Canada), New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, provision was made for taking in the remaining provinces and portions of British North America, as opportunity might offer. The immediate effect of Confederation was to relax the tension between Upper and Lower Canada, and, by providing a wider stage of action, to give a new and enlarged political life to all the provinces thus brought into union.

The political history of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia in the period preceding Confederation ran parallel in many respects with that of Upper and Lower Canada. As already mentioned New Brunswick became a separate province in 1784. Its first Legislative Assembly, consisting of twenty-six members, met at Fredericton in January, 1785. It was to be expected that the Home authorities, dealing with sparse populations scattered over the vast extents of territory acquired by British arms, should have provided for them institutions and methods of administration to some extent of a paternal character. It was natural that the point of view should in the first place be the imperial one; and as institutions root themselves in time and by force of custom two conflicting tendencies came into operation at the same time, the tendency of the strictly colonial system to consolidate itself and to form vested interests, and the tendency of increasing population to demand for the people a fuller measure of political initiative and a well defined responsibility of the Government to public opinion. The main difference between the Maritime provinces and the Canadas in this respect was that, while in the latter violent means were employed in order to bring about reforms, in the former constitutional methods were strictly adhered to. In Nova Scotia the cause of reform found its strongest champion in Joseph Howe; in New Brunswick the lead was taken by such men as E. B. Chandler and L. A. Wilmot. For all the provinces the full recognition and establishment of the principle of responsible government may be assigned to the years 1848 and 1849.

The principle of representation according to population was put into operation by the British North America Act, so far as the constitution of the elective chamber, henceforward to be called the “House of Commons,” was concerned. In the old Canadian Legislature each section of the province returned sixty-five members. The new province of Quebec retained this measure of representation, and the other provinces were allowed representation in the same proportion as sixty-five bore to the population of the province of Quebec. In the Upper House, or Senate, equality of representation was established as between Ontario and Quebec, twenty-four seats being given to each, while New Brunswick and Nova Scotia were allowed twelve each. The debts of the several provinces were equitably provided for, and a payment at so much per head of population was made for provincial expenses out of the federal revenue arising from customs, excise, etc. In the course of a few years certain financial readjustments which local circumstances seemed to call for were made in the case of both Nova Scotia and of New Brunswick.

In the old province of Canada the extinction of the Hudson's Bay Company's claims in Rupert's Land and the Northwest, and the acquisition and organization of those vast territories had at different times occupied the attention of the Government and Legislature. In the year 1856 the subject was much debated in the Press, and in 1857 Chief Justice Draper was sent to England to discuss the matter. In the Speech from the Throne in the year following the Governor General said: “Correspondence in relation to the Hudson's Bay Company and its territory will be laid before you. It will be for you to consider the propositions made by Her Majesty's Secretary of State for the Colonies to the Company and to weigh well the bearings of these propositions on the interests and rights of Canada. Papers will also be submitted to you showing clearly the steps taken by the Provincial Government for the assertion of those interests and rights and for their future maintenance.”

It was not however till Confederation had been accomplished that definite action was taken by the Legislature of Canada in relation to this very important matter. In the first session of the Dominion Parliament an address to the Queen was adopted embodying certain resolutions that had been moved by the Hon. William McDougall. Messrs. McDougall and Cartier were sent to England to follow the matter up, and after some months of negotiation they succeeded in arranging for the transfer on satisfactory terms.

The first province formed out of the ceded territory was Manitoba. It is needless here to enter into the difficulties arising from the apprehensions of the half-breed population that certain rights regarded by them as prescriptive would not be duly protected, which retarded for some months the accession of the new province to the Dominion. An expeditionary force under Sir Garnet (later Field Marshal Viscount) Wolseley was sent to the disturbed region, but before its arrival at Fort Garry (September 24, 1870) all opposition had ceased. The date of the legal creation of the province was July 15, 1870. On the same date the Northwest Territories were placed under a territorial government. The subsequent development of the whole western region, the enlargement (twice) of the limits of Manitoba, the creation out of the Northwest Territories of the two provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta and of the Yukon Territory are matters within recent memory. The six maps on pages 19 to 21 illustrate the political development of Canada from 1841 to the present time.

At the date of Confederation British Columbia had a separate Provincial Government, the establishment of which dated from 1858. The Provincial Legislature having passed resolutions in favour of union with Canada on certain specified conditions, which embraced the construction of a transcontinental railway and the maintenance of a sea service between Victoria and San Francisco, an address to the Queen praying that the measure should be carried into effect was adopted by the Parliament of the Dominion, and on July 20, 1871, the Pacific province joined the Confederation. Two years later (July 1, 1873) Prince Edward Island was admitted. Negotiations for the inclusion of Newfoundland have at different times taken place, but hitherto without result.

In the year preceding Confederation the Reciprocity Treaty negotiated with the United States in 1853 was abrogated. The effect was temporarily depressing so far as Canada was concerned, but the main result was to create an active search for other markets, and in 1866 a commission, headed by the Hon. Wm. McDougall, was sent to the West Indies and South America with that object. An attempt was nevertheless made to obtain a renewal of the treaty, and delegates were sent to Washington to discuss the matter. Their mission was wholly unsuccessful. It was in the same year, 1866, that an attack was made by the Fenians, chiefly soldiers from the disbanded Union armies, on the Niagara frontier. In an engagement which took place near the village of Ridgeway, the Canadian volunteers sustained, for their numbers, considerable loss; but the enemy, hearing of the advance of a body of regular troops, made their escape to the American side, where they were arrested by the civil authorities.

An important event in the early history of the Dominion was the negotiation of the Treaty of Washington (1871). The abrogation of the Reciprocity Treaty, five years earlier, had put an end to the fishing rights in British waters which, under that treaty, the Americans had enjoyed. American fishermen were, however, slow to recognize or accept the change. Treaty or no treaty, they were bent on enjoying the privileges to which they had grown accustomed. Some of their vessels having been seized and confiscated much ill-feeling arose; and, as the Alabama claims were still unsettled, the condition of things as between Great Britain and the United States was highly unsatisfactory, not to say alarming.

It was in these circumstances that it was decided to refer the principal matters in dispute or in doubt between the two countries to a Joint Commission, consisting of five members from each; and the Canadian Prime Minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, was appointed as a member on the British side in order that the interests of Canada might have full representation. The Commission accomplished some useful work, inasmuch as it provided a means for the settlement of the Alabama claims and of the San Juan question; but while the Canadian Parliament ratified the clauses relating to Canadian interests the feeling was general that those interests had in a measure been sacrificed. The fisheries were to be thrown open to the Americans for a period of ten years, and a Commission was to decide as to the compensation to be paid to Canada for the privilege. The Americans were to have free navigation of the St. Lawrence and the use of the Canadian canals on the same terms as Canadians. The latter were to have the free navigation of Lake Michigan. It had been hoped that some compensation might be obtained for losses inflicted by the Fenians, but the Americans, notwithstanding their eagerness for the payment of the Alabama losses, refused absolutely to entertain the proposition.

The Government that was formed to carry Confederation underwent an important change before that event took place. Mr. George Brown resigned in the month of December, 1865, the assigned reason being a difference of opinion with his colleagues as to the expediency of pushing negotiations with the Government at Washington on the subject of Reciprocity, Mr. Brown being opposed to such action. Later, when Confederation had been fully accomplished, a political question arose, namely, whether or not the Government should retain its coalition character. It may here be mentioned that, to mark that important event, Mr. J. A. Macdonald had been made a K.C.B., and that shortly afterwards a baronetcy had been conferred on Mr. G. E. Cartier, and knighthoods on Messrs. A. T. Galt and H. L. Langevin. Sir John Macdonald was desirous of retaining his Reform colleagues, while Mr. Brown held that they should retire: they decided to remain.

The Imperial Government had for some years been withdrawing its troops from Canada, and in November, 1871, the last British soldiers were withdrawn.

The first election under Confederation gave the Government a decided majority. The second, held in 1872, was again favourable to the Government, though its popularity had been somewhat lessened by the dissatisfaction with the Treaty of Washington, ratified the year before. Revelations that were made in the following year, as to the means by which election funds had been obtained by the Government brought on a Cabinet crisis. To avoid impending defeat in the House of Commons Sir John Macdonald resigned (November 5, 1873) and Mr. Alexander Mackenzie, the recognized leader of the Opposition, was called upon to form a Government. A general election held early in the following year gave a large majority to the new Administration.

The first election under Confederation gave the Government a decided majority. The second, held in 1872, was again favourable to the Government, though its popularity had been somewhat lessened by the dissatisfaction with the Treaty of Washington, ratified the year before. Revelations that were made in the following year, as to the means by which election funds had been obtained by the Government brought on a Cabinet crisis. To avoid impending defeat in the House of Commons Sir John Macdonald resigned (November 5, 1873) and Mr. Alexander Mackenzie, the recognized leader of the Opposition, was called upon to form a Government. A general election held early in the following year gave a large majority to the new Administration.

The agreement made with British Columbia was that the transcontinental railway should be begun within two years after its becoming a province of the Dominion, and the question was engaging the attention of Sir John Macdonald's Government in 1872, when an Act was passed defining the conditions on which a contracting company might construct the line. The change of Government involved to some extent a change of policy on the railway question; but the Mackenzie Government having been defeated in the general election of September, 1878, and Sir John Macdonald having returned to power with a large parliamentary support, the conduct of the enterprise passed again into his hands. The plan first adopted was that the railway should be built in sections by the Government; but the difficulties involved were such that in 1880 the work was turned over to a syndicate which undertook to form a company to build a road from a point near North Bay, Ont., to the Pacific, for a cash payment of $25,000,000 and 25,000,000 acres of land in what is known as the “Fertile Belt.” The contract embraced other points which cannot here be detailed. Certain sections of the line which the Government had already built, or were at the time building, were also to be turned over to the company. This was the origin of the Canadian Pacific railway, which has since become one of the most powerful corporations in the world, controlling not less than 11,500 miles of railway.

In connection with Confederation a guarantee had been given by the Imperial Government of a loan of £3,000,000 sterling towards the construction of the Intercolonial railway, a work the necessity of which had long been felt by the provinces concerned, and which many previous efforts had jointly been made to carry into execution. There was nevertheless considerable delay in the construction of the line, which was not opened through its entire length till the year 1876. That year was further marked by the establishment of the Supreme Court of Canada as a court of appeal from provincial jurisdictions. In the following year an International Commission, created under the terms of the Treaty of Washington, to determine the amount to be paid to Canada for the ten years' concession made to the United States in the matter of fisheries, and which had sat at Halifax, gave an award in favour of Canada of $5,500,000.

The change of Government in 1878 was generally recognized as due to a growing feeling throughout the country in favour of a protective policy for Canada, a policy which the Conservative Party had adopted, but to which the Liberal leader, Mr. Mackenzie, was strongly opposed. A tariff, which may be taken as constituting the first phase of what has since been known as the “National Policy,” was introduced by the then Finance Minister, Sir Leonard Tilley, in the session of 1879, the effect of which was to raise the customs duties to an average of about 30 per cent. The first tariff adopted under Confederation, while establishing free trade between the provinces, had imposed uniform duties of 15 per cent, on all foreign goods (including British). This had been increased to 17 1/2 per cent, during the Liberal regime, which had coincided in the main with a period of great financial depression. The new tariff was thus a decided step in the direction of protection, and was held in a short time to be justified by its effect on the trade of the country.

The year 1880 was marked by the death, at the hands of an assassin, of the Hon. George Brown, who for many years had been the leading exponent of Reform principles in Upper Canada; and also by the transfer to Canada by Imperial Order in Council of all British possessions on the North American continent not previously specifically ceded.

In the fall of the year 1878 the Marquis of Lome (later the ninth Duke of Argyll), accompanied by H.R.H. the Princess Louise, had come to Canada as Governor General. Two important societies owe their origin to his initiative, the Canadian Academy of Arts, established in 1880, and the Royal Society of Canada, established in 1881, both of which have been influential in advancing the higher life of the Dominion.

The earliest institutions for higher education were opened in the Maritime provinces. The University of New Brunswick claims priority, as it was founded in 1800, but for years its activities were suspended and its reopening dates only from 1859. Dalhousie College, Halifax, on the other hand has been in continuous operation since 1818. McGill College was established at Montreal in 1811 and the McGill University was incorporated in 1821. A charter was granted in 1827 to King's College, Toronto, which under a more liberal constitution became in 1843 the University of King's College and in 1849 the University of Toronto. Victoria University, a Wesley an institution, was established at Cobourg in 1836, and Queen's College, a Presbyterian one, in 1841. Laval University, in the city of Quebec, and Trinity College, in Toronto, both date from 1852. A quarter of a century elapses and a well-equipped university is found in operation in Winnipeg, seven years only after the admission of the Red River territory to the Dominion. To-day there are universities established at Saskatoon, Sask., at Edmonton, Alberta, and at Vancouver, B.C.

By the British North America Act public education is constituted a function of the Provincial Governments, and each province therefore maintains its own educational system. A Royal Commission on Industrial Training and Technical Education was appointed by the Dominion Government on June 22, 1910. The members visited several of the most advanced countries of the world for the purpose of studying methods and results, and have presented a voluminous and highly instructive report.

A slight reference has been made to certain troubles incident to the organization of a Government for the province of Manitoba in 1869-70. After a lapse of fifteen years the same elements in the population which had resisted the political change then accomplished broke out into open rebellion (March, 1885) not, however, within the limits of Manitoba, but in the Prince Albert district of the territory of Saskatchewan. Militia regiments were despatched from the different eastern provinces under the command of General Sir F. Middleton to the scene of disturbance, and order was in the course of a few months completely restored, though not without some loss of life. The same year witnessed the completion of the Canadian Pacific railway, the last spike having been driven by Sir Donald A. Smith (later Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal) at a point called Craigellachie on November 7. Canada now possessed within her own territory a line from ocean to ocean, though the first through train from Montreal to Vancouver did not pass over the line till the month of June following.

General elections were held in the years 1882, 1887, and 1891, and on each occasion the Government of the day was sustained. On the last occasion mentioned the Conservative leader, Sir John Macdonald, threw himself into the campaign at a very inclement season of the year (February and March) with his accustomed energy, but the strain was too great for his years and, when Parliament met on April 29, he was in visibly impaired health. On June 6 he died, aged 76. By common consent he had done much to shape the political history of Canada. His gifts as leader and statesman were acknowledged not less freely by opponents than by supporters. He was succeeded as premier by Sir John Abbott, who only held the position for a year and a half, when the state of his health compelled him to retire. The Government was then reconstructed by Sir John Thompson (December, 1892) who, having gone to England on public business, died very suddenly at Windsor Castle on December 12, 1894. Signal honour was paid to his remains by their conveyance to Canada in a British war vessel, the Blenheim, the arrival of which at Halifax has been made the subject of an impressive painting by the Canadian artist, Mr. Bell Smith.

Three Conservative premiers had now died in the space of three years and a half. Sir Mackenzie Bowell was then placed at the head of an Administration in which certain elements of disunion soon began to manifest themselves. On April 27, 1896, Sir Mackenzie yielded the reins of government to Sir Charles Tupper, who had for some years before been filling the office of High Commissioner for Canada in London. A question relating to the public schools of Manitoba had now become acute. Upon the establishment of the province a system of “separate schools” was organized, under which the control of Catholic schools was left in the hands of the Catholic section of a general School Board. The cancelling of this arrangement in 1890 led to protests and a demand for the “remedial legislation” provided for by the British North America Act in cases in which educational rights enjoyed by any section of the population before Confederation were abridged or disturbed by subsequent legislation. The Privy Council, to whom the case had finally been appealed, decided that such remedial legislation was called for; and the Dominion Government was consequently under obligation to introduce it. The question was much discussed before and during the general election of June, 1896, but to what extent it influenced the result is doubtful. The Government sustained a decisive defeat (June 23, 1896).

The death of Sir John Macdonald had been followed within a year by that of the Hon. Alexander Mackenzie (April 17, 1892). The latter had not however been leader of the Liberal party for the last five years of his life, the Hon. Wilfrid Laurier having been elevated to that position after the general election of 1896. The new Government of which he was the head was sworn in on July 13. In some quarters it was hoped, in others apprehended, that the policy of the new Administration would embrace a serious reduction of the tariff established by their predecessors. No fiscal changes, however, of any moment were made. It was recognized that the business of the country had adapted itself to the measure of protection provided and that any violent change in that respect would be unwise. One of the earliest measures adopted was the reduction by one-fourth of the customs duties charged upon articles the growth, produce, or manufacture of the United Kingdom, or of certain specified British colonies, or of any others, the customs tariff of which was as favourable to Canada as the proposed reduced, or preferential tariff to the colonies in question. An impediment to the immediate carrying into effect of this arrangement was found in the existence of certain commercial treaties made by Great Britain with Germany and Belgium; this difficulty having been removed by the denunciation of the treaties in question, the reduced inter-Imperial tariff went into operation on August 1, 1898. From the application of this tariff, wines, spirituous liquors and tobacco were excepted.

The “British Preference,” as it was called, was further increased to one-third in the year 1900. Important and beneficial changes had meantime been made in the postage rates. The Canadian domestic rate of three cents per ounce was reduced to two cents on January 1, 1899, and the same rate was established between Canada and Great Britain, and gradually extended to the great majority of the British colonies. It should be mentioned that under the former Liberal Government Canada had joined the Universal Postal Union (August 1, 1878) by which a general though not universal postage rate of five cents per half ounce was established between the different signatory countries.

In a general election which took place on December 7, 1900, the Government was sustained. Parliament met on February 6, and on the 8th passed an address of condolence to King Edward VII on the death of Queen Victoria (January 22, 1901). In September of the same year, the Duke and Duchess of York (now King George V and Queen Mary) visited Canada and were enthusiastically received. The date fixed for the Coronation of King Edward was June 26, 1902, but the sudden and alarming illness of His Majesty made a postponement necessary, and the ceremony was performed on August 9. It had been suggested by the Colonial Secretary (Mr. Chamberlain) in the previous month of January that advantage should be taken of the presence in London of the Premiers and probably other Ministers of the self-governing colonies of the Empire on this occasion to discuss various matters of Imperial import, and a Conference at which he presided, was opened on June 30 and remained in session till August 11. At this Conference a number of important resolutions were adopted, including one recognizing the principle of preferential trade within the Empire and favouring its extension, and another recommending the reduction of postage on newspapers and periodicals between different parts of the Empire, to which effect has since been given.

The development of Canada during the last twenty years, in population, commerce and industry has been very marked, and has been especially conspicuous in her western provinces. The Northwest Territories, which at first were governed from Winnipeg—the Lieutenant Governor of Manitoba being also Lieutenant Governor of those territories—were organized as the provisional districts of Assiniboia, Saskatchewan, Alberta and Athabaska (May 17, 1882), under a Lieutenant Governor of their own, with the seat of government at Regina. With the growth of population they rapidly advanced towards provincial status, and on September 1, 1905, the four territories were organized as the two provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta, the capital of the first being fixed at Regina, and of the second at Edmonton. Their subsequent progress has been even more remarkable owing to the large volume of population they have annually received both from the United States and from European countries. The discovery of gold in the Yukon country led to its organization as the Yukon Territory (June 13, 1898), and as such it returns a member to the Dominion Parliament. The mining of gold and silver in Canada led to the establishment at Ottawa (January 2, 1908) of a Branch of the Royal Mint, where gold, silver and copper coins are now struck for circulation in the Dominion. Another interesting branch of the public service which has recently assumed much importance, being now organized as a separate department, is the Dominion Archives, where an ever-increasing mass of papers, manuscript and printed, is being daily made available for consultation and study.

Two very important arbitrations in which Canada was much interested have taken place within a recent period between Great Britain and the United States, the first relating to the rights possessed by British subjects in the seal fisheries of Behring Sea, and the second as to the boundary between Alaska (purchased by the United States from Russia in 1867) and Canada. In the first case the claims advanced, mainly in behalf of Canada by Great Britain, were fully upheld (September, 1893). In the second there was some disappointment in Canada over the award (October, 1903) which did not however in any serious degree affect Canadian interests.

The year 1908 marked the completion of three centuries of Canadian history, reckoning from the foundation of Quebec by Champlain in 1608. As the date approached various plans for its due celebration were discussed. The three centuries in question were divided into two almost exactly equal portions by the taking of Quebec in the year 1759. It seemed desirable therefore that steps should be taken, not only for the celebration of so interesting an anniversary, but also for instituting some permanent memorial of the birth of a new Canada in the shock of two mighty forces on the Plains of Abraham. The situation and scenery of Quebec furnished an incomparable stage for spectacular and dramatic effects; and a number of suitable historic pageants were carried through with immense success in the week beginning July 24 before a vast multitude of spectators drawn from every part of Canada and from far beyond her borders. The effect of the celebration was heightened by the presence of the Prince of Wales (now H. M. King George V), whose arrival in the battleship Indomitable had been preceded by that of a squadron of four other battleships and two protected cruisers. The occasion was marked also by the complimentary visit of one French and two United States war vessels. A most interesting feature was a military review in which 12,000 Canadian troops and 3,000 marines and sailors from the battleships took part. Field Marshal Lord Roberts, who was present, cabled to the King his great satisfaction with the precision, order and organization manifested in the manoeuvres. The celebration as a whole formed a most impressive and memorable moment in the national life of Canada.

The movement for the perpetuation of the memories of 1759-60 took the form of a scheme for the purchase of the ancient battlefield and its conversion into a National Park, with which might be connected an historical and military museum. Liberal contributions have been made towards it by the Dominion Government, the several Provincial Governments, and many leading corporations and individuals. The scheme is now in course of realization.

A celebration that was in a manner preliminary to that of July, 1908, was one held at Quebec on May 6 of the same year to mark the two hundredth anniversary of the death of the celebrated and justly venerated Laval, the first bishop of Quebec. The enthusiasm which it evoked was unbounded, and it will long be remembered as an event of the highest interest and significance.

In the year 1898 the difficulties which had arisen between the British Government and the Transvaal, on the subject of the legal disabilities under which British subjects in that country were labouring, resulted in a declaration of war by the Republic. Sympathy with the Mother Country in a conflict on which she had entered most reluctantly, and which was being waged in a far-distant region under conditions of great disadvantage for the British forces, became so acute in Canada—as also in New Zealand and Australia—that the Government felt impelled to take a share in the struggle by sending Canadian troops to the scene of action. A first contingent of the Royal Canadian Regiment left Quebec in the steamer Sardinian on October 30,1899. Others followed, sailing from Halifax January 21, January 27, and February 21, 1900. Altogether 1,150 officers and men of this force were sent to South Africa. To these were added a detachment of 398 Mounted Rifles, one of Royal Canadian Dragoons, numbering 379, and an artillery corps of 539 officers and men. Over and above these Lord Strathcona sent out at his own expense a special mounted force of 597 officers and men. In all, 3,092 officers and men were despatched to South Africa in 1899-1900. The Canadian troops did not fail to distinguish themselves by their bravery in the war, particularly in the battle of Paardeberg (February 27, 1900) in which the Boer general, Cronje, was forced to surrender. In 1901 there was a further enlistment in Canada of Mounted Rifles to the number of 900, at the expense of the Imperial Government, and also of 1,200 men for service in the South African constabulary.

This practically brings up to date a record in briefest outline of the leading events of Canadian history that are not still matters of current controversy. For more detailed particulars regarding recent events the reader may be referred to the notes in the Year Book since 1905. In those volumes are also recorded statistically the extraordinary economic progress of Canada which has marked the opening years of the twentieth century. The construction of new railways, the constantly increasing tide of immigration from the United Kingdom, from the United States and from countries of the European continent, and the immense progress in all forms of production (agriculture, forestry, fisheries, mines and manufactures) have combined, within a relatively short period, to raise the Dominion of Canada to a position of real influence in the world's markets, and to show that the Canadian people are developing the splendid resources of their country with energy, persistence and success.