Common menu bar links

History of the Great War of 1914 to 1918 (1916)

Operations on the Western Front, 1916

In December, 1915, General Joffre was appointed to command all the French armies, and was succeeded by General de Castelnau in command of the French troops engaged in France. Sir Douglas Haig succeeded Sir John French in command of the British forces in France, and late in December, 1915, the Indian army corps was transferred to Mesopotamia. At the commencement of the year, the German forces were probably much outnumbered on the western front, but they held dominating positions which were not easily attacked. In the month of January, their armies on that front were heavily reinforced and resumed the offensive at several points, apparently to test the strength of the allied positions and keep

them in uncertainty as to their future intentions. On the morning of February 21, a tremendous artillery preparation began in the sector of Verdun, followed by a fierce infantry attack in the- afternoon, which carried several of the French first line positions. Their assaults were continued on the two following days, and by the night of the 2 they had captured the whole of the first line of the French intrenchments on the right bank of the Meuse, and taken several thousand prisoners at the cost of terrible losses. The French garrison was continually reinforced, and kept well supplied with ammunition. It is stated that four thousand motor trucks were constantly employed on this service, and two hundred thousand men brought up to hold the defences. The struggle continued with a dreadful sacrifice of life on both sides, with little intermission until March 22. The fort of Douaumont, a very commanding position, was taken by the Germans, but otherwise their gains were insignificant. A lull in the fighting occurred between the 22nd and the 28th of March, when the attacks were renewed on both banks of the river, and continued until April 25. Three fortified villages which had been converted by an intense bombardment into shapeless heaps of ruins were taken, but a great final assault utterly failed, and the assailants never succeeded in really approaching the main defences of the place.

them in uncertainty as to their future intentions. On the morning of February 21, a tremendous artillery preparation began in the sector of Verdun, followed by a fierce infantry attack in the- afternoon, which carried several of the French first line positions. Their assaults were continued on the two following days, and by the night of the 2 they had captured the whole of the first line of the French intrenchments on the right bank of the Meuse, and taken several thousand prisoners at the cost of terrible losses. The French garrison was continually reinforced, and kept well supplied with ammunition. It is stated that four thousand motor trucks were constantly employed on this service, and two hundred thousand men brought up to hold the defences. The struggle continued with a dreadful sacrifice of life on both sides, with little intermission until March 22. The fort of Douaumont, a very commanding position, was taken by the Germans, but otherwise their gains were insignificant. A lull in the fighting occurred between the 22nd and the 28th of March, when the attacks were renewed on both banks of the river, and continued until April 25. Three fortified villages which had been converted by an intense bombardment into shapeless heaps of ruins were taken, but a great final assault utterly failed, and the assailants never succeeded in really approaching the main defences of the place.

Fighting began again during the first week in May and lasted on the left bank of the Meuse, until the first of July. Fort Vaux was taken on June 6, and on June 9 one hundred thousand men were employed on a front of only three miles in a desperate assault on the heights of Thiaumont which they eventually carried. The British offensive on the Somme caused a great diversion of troops in that direction and compelled the Germans thenceforth to remain on the defensive in this sector.

The long delayed allied attack on that part of the German lines was preceded by a tremendous bombardment lasting continuously for five days on a broad front, by frequent raids at night with small parties to ascertain its results, and by successful assaults on the German aircraft. Many of their observation balloons were brought down, and allied aeroplanes bombed divisional headquarters and the principal railway stations in rear. Decisive ascendancy in the air was secured in the sector selected for the main offensive, and the concentration of troops was carried out with all possible secrecy. The British forces had been heavily reinforced and two new armies formed. A large additional frontage was taken over by them from the French on the Somme. The time for the assault was fixed for 7.30 a.m. on July 1. Sir Henry Rawlinson commanded the British troops allotted for the attack, which was made on a front of twenty miles against the Thiepval ridge, while the French attacked on an eight mile front on both sides of the river Somme, to their right, under the orders of General Foch. The British attack failed on the extreme left, owing to insufficient preparation, but the German first line was pierced on a front of sixteen miles in the face of an obstinate resistance, chiefly from machine guns concealed in positions where they could not be reached by artillery fire. The French were successful all along their front, as an attack there seems to have been somewhat unexpected. The advance was continued on July 2 and 3. On the following day, operations were delayed by heavy thunderstorms, but the French continued to gain ground. Heavy reinforcements had been received by the Germans who began violent counter-attacks upon the British.

On the 7th a division of the Prussian guard made a desperate attack on the British position near Contalmaison, which was repelled with great loss, many prisoners being taken. Fighting continued day after day with great fury, and the Germans were driven from a large portion of their second line by the end of the month. Numerous desperate struggles took place for small positions. The fighting in the month of August continued daily with slow but steady gains of ground on the part of the Allies, yet at no point did they succeed in breaking through. The artillery bombardment was continued with unprecedented energy. On some occasions, ninety thousand shells were fired within an hour by the allied guns, and in certain instances, more than a million inside of twenty-four hours. A great force of cavalry and horse artillery was held in readiness close in rear, with the intention of taking advantage of a breach in the enemy's position. A great joint attack was delivered with considerable success on a front of forty miles on September 3, in which twenty-eight allied divisions were engaged. On September 14 and 15, the British assaulted the German positions near Courcelette, which was carried by the Second Canadian Division. Many heavy armoured landships or “Tanks” were first brought into action on this occasion with great success, and the German losses were extremely heavy, as they had massed troops for a counter attack in their front trenches. On September 26, the First Canadian Division captured the Hessian trench and other British troops carried the great Hohenzollern redoubt, noted for its elaborate system of defences and deemed impregnable. Next day they carried the Stuff redoubt and two thousand yards of adjacent trenches, and on the 28th the Schwaben redoubt which commanded the valley of the Ancre River. During the first week of October, operations were greatly impeded by heavy rains, but on the 7th the British made an advance of twelve hundred yards on an eight mile front. The French undertook a vigorous and skillfully prepared offensive near Verdun on October 24, when they recaptured Douaumont, and in a few hours regained nearly all the ground they had lost on the east side of the Meuse since the beginning of the German offensive, taking several thousand unwounded prisoners. Operations were then begun against Fort Vaux, which was evacuated by the Germans on November 2, as a result of a furious bombardment. The weather during November was highly unfavourable for operations on the entire western front owing to incessant rains which soon converted the country into a sea of mud; still on November 12, the French captured Saillisel, a strong position north of the Somme and pierced the German fourth line. Next day the British attacked on both sides of the river, favoured by a dense mist, and penetrated the German intrenchments to a depth of a mile on a front of three thousand yards, taking five thousand prisoners. Many heavy bombardments and trench raids took place during the remainder of the year without appreciable gain on either side.

After several days’ artillery preparation, the French executed a successful attack on the German lines east of the Meuse, near Verdun, and carried their intrenchments on a front of six miles, taking nearly twelve thousand prisoners and many guns on December 15.

The German offensive at Verdun had failed disastrously. The allied offensive had also fallen far short of the objectives in view. Both operations entailed immense sacrifices in life and enormous expenditures of ammunition.

Operations on the Italian Front, 1916

The weather prevented active operations on this front during the early months. The snow was deep, and misty weather interfered with the effective use of artillery. The rugged character of the country made supply of the opposing forces a task of extreme difficulty. Continuous preparations had been carried on by the Austrians during the winter and early spring for an offensive on a great scale in the Trentino, when the weather became favourable. In March all their main positions were fiercely bombarded to prevent reinforcements from being sent to the French front. The Austrians had brought large bodies of men from the Russian front, and had conducted all their operations with such profound secrecy that when their principal attack commenced, the Italians were ill prepared to oppose it. On May 14 the Austrians began a violent bombardment of the Italian positions on a front of many miles. They employed upwards of two thousand guns, of which eight hundred were of very large caliber, among them forty howitzers of the largest class. The force assembled for this attack numbered 350,000. The infantry assault began on May 18, and continued to gain ground in the valleys of Adige and Brenta until June 2, when it was checked upon a new line many miles in rear. The Austrians reported the capture of thirty thousand prisoners and three hundred guns. For the next two weeks they continued to attack the new Italian positions from day to day on various parts of the line, and on one occasion along its whole front, but failed to make any important advance. Three divisions were then hastily withdrawn to oppose the Russian offensive in Galicia. On June 25, the Austrian retreat began to a selected position protected by strong rear guards, but was not effected without serious losses. An Italian offensive had been planned to take place on the Isonzo, simultaneously with the allied attack on the Somme and the Russian invasion of Galicia, having Gorizia as its main objective. This had been postponed on account of the Austrian advance in the Trentino. The attack began on August 6, and Gorizia was taken three days later. The advance was continued successfully until August 17, when it was checked. Their offensive on this front was not resumed until October 11. Several lines of trenches were captured on that and the following day. On the Carso plateau, a further advance was made on November 1 and 2, when a portion of Austrian intrenchments was carried and many prisoners taken. Further active operations were prevented by bad weather.

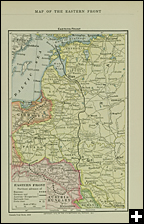

Operations on the Russian Front, 1916

At the beginning of the year the Russians still occupied a defensive line in front of their railway, extending from the gulf of Riga to the frontier of Rumania, over seven hundred miles in length. Here they repelled every attempt of the enemy to pierce their positions and reach the railway. On December 23, 1915, they commenced an offensive to divert attention from their projected operations in the Caucasus. Fierce fighting continued until the middle of January, 1916, along the Strypa and Styr rivers without any important success on either side. On March 16 the Russians advanced towards Vilna to relieve the pressure at Verdun and possibly to anticipate a German offensive in the vicinity of Riga. Little progress was made before a thaw put an end to operations at the end of the month. Another great offensive on their part began in June, with three army groups acting under the immediate direction of the Czar with General Alexieff as chief of staff. This movement opened with simultaneous attacks on selected portions of the Austrian line, south of the Pripet marshes on June 4. Both the opposing Austrian armies were forced back with heavy loss in prisoners, chiefly of discontented soldiers who voluntarily surrendered by entire units. Lutsk was taken on June 6 and Dubno on the 8th. The Austrians were then heavily reinforced by troops from the line north of the marshes and by some German troops from Verdun and Austrians from the Trentino, who were hurried across from the other fronts by railway. The Russians reported the capture of nearly two hundred thousand prisoners and more than two hundred guns. It was believed that the principal Austrian armies had been reduced to half their former strength. The Austro-German forces commenced their counter-offensive on June 16, and continued it until the end of the first week in July, driving back the Russians for many miles. The Russians renewed their advance on July 4 with considerable success. On July 16 they again attacked and advanced on the city of Brody which was taken on the 28th. Their other operations farther south were also successful, and they cut the railway leading from Galicia into Transylvania. On August 2 von Hindenburg was given supreme command of the Austrian and German armies on the entire eastern front, and under his able direction a vigorous effort was made to check their further progress. Indecisive fighting continued with little interruption during the remainder of that month.

On August 27 Rumania published a declaration of war upon Austria-Hungary, and made a surprise attack upon the troops guarding the passes of the mountains on the Transylvanian frontier. This step was undoubtedly accelerated by the recent Russian successes. Two days later, the Russian army of the Danube began its march southward through Rumania and crossed the Danube. On the same day Field Marshal von Hindenburg was appointed chief of staff of the German army in place of General von Falkenhayn, who took command of the Austrian and German forces assembling for operations against Rumania. The Rumanian army invaded Transylvania, and in five days advanced fifty miles. It occupied Kronstadt, the commercial capital of the province, and several other large towns. An army of Bulgarians, Germans and Turks under von Mackensen, entered the Rumanian province south of the Danube, and gained a considerable success by the capture of the fortress of Turtukai and the occupation of Silistria. Mackensen was afterwards unsuccessful in a battle lasting for five days commencing on September 16, and was compelled to retire some distance. In the beginning of October the Rumanians were expelled from Transylvania, and forced to retire into their own country. On October 23 Mackensen captured Con-stanza, the chief Rumanian port on the Black Sea, and advanced upon the great bridge over the Danube, at Cernavoda, which was destroyed by the Rumanians. In the middle of November von Falkenhayn's army forced the mountain passes and advanced upon Bucharest. Mackensen's troops crossed the Danube and formed a junction with the army under Falkenhayn. The Rumanians were decisively defeated in a battle on the Arges River, a few miles southwest of Bucharest on December 3. That city was occupied by the Germans three days afterwards. The remnant of the Rumanian army joined the Russian troops which had entered eastern Rumania, and took up strong defensive positions along the Sereth River.

The Italians had landed two divisions in Albania in December, 1915, and advanced as far as Durazzo, which they held until February. An. Austrian army invaded Montenegro in the beginning of the year, and captured Cettinje, the capital, on January 13. Ten days later they took Scutari, and advanced towards Durazzo, which was evacuated by the Italians and occupied by the Austrians on February 26.

At a conference of the Allies it had been decided that Saloniki should be retained as an indispensable base for future operations, and a strong defensive position was prepared far in advance for the protection of the city. A large part of the allied armies engaged in the Gallipoli peninsula were after its evacuation transferred to Saloniki. The remnants of the Serbian army were taken to the island of Corfu for a long period of rest and recuperation after the privations and sufferings of their terrible retreat. These troops, numbering in all upwards of 100,000 effective men, were then transported to Saloniki, to reinforce the allied armies there. The Allies began a vigorous offensive early in September on a front of one hundred and twenty-five miles, and the Bulgarians were steadily driven back in the direction of Monastir. Fighting continued with little intermission until November 19, when that town was taken by the Allies and proclaimed as the temporary capital of Serbia.

The War in the Caucasus and Mesopotamia, 1916

The Russian army in the Caucasus was strongly reinforced in December, 1915, and January, 1916. Its offensive operations were considerably hastened by the evacuation of the Gallipoli peninsula by the allied British and French armies, by which a large Turkish force would be released for service elsewhere. In the midst of severe winter weather an advance was commenced upon Erzerum, the principal Turkish fortress in Armenia. The Turkish army assembled for its protection was routed on January 18, and the fortress evacuated by the Turks on February 16. Another army supported by a fleet on the Black sea took Trebizond on April 18, and the conquest of Turkish Armenia was practically completed by the end of August.

The British division commanded by General Townshend had been besieged at Kut-el-Amara since December 3, 1915. Several determined attacks were repulsed, and the Turks then decided to reduce the garrison by starvation. A relieving column commanded by General Aylmer, after advancing a considerable distance and driving a covering force from several positions, was finally checked on April 23. On April 25 Townshend's division, which was reduced to less than 9,000 troops, was obliged to surrender.

The effective defence of the Suez Canal was an object of great importance to the Allies. Garrisons had been established at posts several miles east of the canal to keep hostile forces at a distance. Some of these were unsuccessfully attacked in the early part of the year and again in August. The British troops then began a systematic advance along the coast, building a railway and constructing a pipe line for the conveyance of water as they went. A commanding position was occupied in the heart of the Sinai Peninsula, and British aircraft bombed several Turkish military posts on the frontier of Palestine.

The War in Africa, 1916

Early in February a considerable German force was driven from Cameroon into Spanish Guinea, where it was interned. The conquest of the province was completed by the surrender of the last German garrison on February 18. General Smuts, in command of the British forces in German East Africa, continued his advance with success. Another British force entered that country from Rhodesia. The Germans were defeated in several small engagements, and the seat of government surrendered on September 4. At the end of the year, only about one quarter of the province still remained in the hands of the Germans.

Naval Warfare, 1916

The command of the sea had passed absolutely into the hands of the Allies. No German merchant ship ventured to make its appearance on the high seas. The German efforts to destroy the commerce of the Allies were limited to the activity of a single light cruiser and to submarine attacks. The British Grand Fleet, having its base in the magnificent harbour of Scapa Flow, encircled by the Orkney Islands, kept undisputed possession of the North sea. The lesser channels into this fine sheet of water were blocked with impassable obstacles, the two large entrances guarded by batteries of heavy guns and a double barrier of steel nets provided with gates to admit the passage of ships. A ring of observation balloons constantly hovered over the islands. Many hundreds of mine sweepers and destroyers kept constant watch and ward without. From this secure lair, thronged with countless colliers, tenders, and store ships of all kinds, squadrons of cruisers, battle cruisers and battle ships attended by aircraft went forth periodically to scour the sea. Communication between all parts of the Grand Fleet was maintained by wireless telegraphy.

On the afternoon of May 31, the battle cruiser division of the fleet, under Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty, consisting of six ships, sighted a squadron of five similar German vessels, which retired southeastward toward the main body of the German fleet, then out of sight. Beatty gave chase at once. It was about 2.30 p.m. Rather more than an hour later, the action began at a range of 18,500 yards. A few minutes afterwards a vast column of black smoke shot into the air to a great height from the “Indefatigable”, the rear ship of Beatty's squadron. When it cleared away that vessel had disappeared. Only two men of its crew of nine hundred were picked up. Shortly afterwards some ships of the fifth British battle squadron came up and opened fire at a range of 20,000 yards, and the third ship in the German line was soon seen to be on fire. A little later the British battle cruiser, “Queen Mary”, blew up from the explosion of her magazine, and only twenty of her crew of one thousand persons were saved. The action had continued on parallel courses for about an hour when three divisions of the German battle fleet were descried approaching. The British squadrons then stood away on a northwesterly course, which would bring them closer to the remainder of their fleet, known to be coming up rapidly. As the surviving battle cruisers were ships of great speed, they easily ran ahead and crossed the course of the German fleet, with the intention of leaving a clear field of fire for their own battle ships and then striking in between the Germans and their base. The fifth battle squadron consequently had to sustain for some time the fire of four German cruisers and several of their battleships. One of the German cruisers however soon fell out of the line and took no further part in the battle. At 6.20 p.m., the third British battle cruiser squadron, commanded by Rear Admiral Hood, came in sight and rashly approached within 8,000 yards of the German battle ships. The “Invincible”, Hood's flag ship, was soon sunk by a shell, and all but six of the crew perished. Sir John Jellicoe then appeared with the two remaining squadrons of battle ships which formed into line and chased the German fleet from the scene of action. Haze, mist, and dense artificial clouds of smoke assisted their escape as evening fell. During the night the German fleet was overtaken by British light cruisers and destroyers which attacked them fiercely and inflicted heavy losses in ships. These losses were carefully concealed at the time, and have never been accurately ascertained. The British battle ship “Marlborough” was struck by a torpedo, but succeeded in returning to port. Besides the ships already named, three armoured cruisers and eight British destroyers were sunk. Three German battle ships were seen to sink, and a fourth was subsequently added to the number on good authority. The next morning found the British fleet in undisputed possession of the scene of action, and the German fleet never afterwards ventured forth, except on one occasion, when it quickly retired again into port on the approach of its opponents.

The submarine activity of the Germans increased in vigour and ferocity. Thousands of small auxiliary vessels were employed in conjunction with the British fleet in detecting and chasing them, and many were destroyed. A French transport was sunk in the Mediterranean and upwards of 3,000 men perished. Two British battleships and one light cruiser were destroyed by mines or torpedoes, and on June 6, the cruiser “Hampshire”, with Field-Marshal Earl Kitchener, the Secretary of War, and his staff on board on their way to Russia, was sunk west of the Orkney isles, and only a single petty officer and eleven seamen were saved out of the entire crew. The destruction of merchant shipping belonging to the Allies and neutral countries by mines and submarines attained serious proportions.

Participation of the British Overseas Dominions and Colonies, 1916

In Canada, an Order in Council passed on January 12, authorized an increase of the Canadian military forces to half a million. Great but fruitless efforts were made to reach that number by voluntary enlistment. An official statement published at the end of the year showed that the number of recruits obtained since the beginning of the war, up to November 30, 1916, aggregated 381,438 of all ranks and branches of the service. The volume of contributions for the different patriotic funds was doubled.

On November 11 Sir Sam Hughes, Minister of Militia and Defence, whose activity and energy had greatly stimulated recruiting and organization, tendered his resignation, at the request of the Prime Minister, as a result of serious differences of opinion in matters of administration. He was replaced by the Hon. A. E. Kemp, already a member of the Cabinet without portfolio. A National Service Board was established for the purpose of increasing enlistments without interfering with important industries. The Canadian troops in France were increased to three complete divisions and formed into an army corps under the command of Sir Julian Byng. Large contingents of Canadian Railway and Forestry troops were also sent to Europe. Many men enlisted for special service in mechanical transport and inland navigation. A Canadian cavalry brigade was formed and, with several batteries of horse artillery, was attached to the Fifteenth British Army corps. Garrisons of Canadian troops were maintained in Bermuda and Santa Lucia.

An official document, published by the Government of Australia, stated that 103,000 men had been recruited by voluntary enlistment in that Commonwealth and sent into the field, and that 100,000 more would be required to replace prospective casualties before July 1, 1917. A bill proposing conscription was submitted to a vote of the electors in October, but defeated by a small majority.

The Union of South Africa continued with success the task it had undertaken of expelling the Germans from that continent.

The troops from New Zealand in Mesopotamia and France were kept up to strength by voluntary enlistment.

Mr. Bonar Law, in a speech in September, made the statement that a larger number of men in proportion to its population had enlisted in the army and navy from Newfoundland than from any other part of the British Empire. The colony contributed, according to information furnished by the Newfoundland Department of Militia, 12,132 men out of a population of 256,290; 7,312 others volunteered their services, but were rejected.

Besides an entire army corps despatched to Mesopotamia to accomplish the relief of Kut, troops from India were sent to Egypt for the defence of the Suez canal, to East Africa, Cameroon, and southern Persia, and garrisons were furnished for Mauritius and Singapore, as well as for the defence of Aden and the new posts on the Afghan frontier. Large contributions to patriotic funds and the military services were made by native rulers and nobles.

Economic Effects of the War, 1916

The great shortage and high price of food in Austria caused serious discontent. A more stringent system of government control of provisions was established with three meatless days a week. In Germany a Food Regulation Board was appointed with extensive powers. Meat cards were made compulsory and a maximum ration of meat was established. Reports of food riots became frequent. A Munitions Department was created at the end of October, and a manpower bill enacted making all able-bodied males between the ages of eighteen and sixty subject to industrial or military service.

In France the cabinet was reorganized and the war services concentrated in the hands of a war council of five members. The post of Commander in Chief of the armies was abolished. General Joffre was appointed technical adviser to the government, but retired soon afterwards. General Nivelle was selected to command all the armies in France on December 12, and General Sarrail, in command of the army at Saloniki, was placed directly under the Minister of War. A law was passed offering bounties for the encouragement of wheat growing.

A conscription bill was passed by the parliament of Great Britain on January 24th, after a short debate. Ireland was excluded from the provisions of this bill. As a result three-quarters of a million of single men were added to the military forces.

The number of war workers had increased by July 1, 1916, to three and one-half millions, of whom 660,000 were women, and 4,000 factories, controlled by government, were producing munitions.

An economic conference of the Allied Governments was held at Paris in June, which framed many drastic proposals.

On Good Friday, April 21, a German submarine landed Sir Roger Casement, with a few companions and a small consignment of arms on the coast of Kerry, in Ireland. Casement was arrested shortly afterwards, and no body of men assembled to meet him or make use of these arms. On April 24, however, a serious insurrection took place in Dublin. Organized bodies of insurgents took possession of the post office, law courts, railway stations, and several adjacent houses. Fighting continued for several days before the rebels were subdued. Less important risings occurred at some small towns elsewhere in Ireland, which were soon put down. A number of prisoners were tried and executed by sentence of court martial. Casement was hanged in London on August 3.

The British Cabinet was re-organized in December, when the Right Hon. David Lloyd George became Premier. A war council of five members was then formed with him at its head.

On February 23, Portugal seized many German merchant ships which had remained in Portuguese ports since the beginning of the war. Four days later Germany protested against this action, and on March 9 declared war on Portugal. The Portuguese Government announced that its action had been taken” as a result of our longstanding alliance with England, an alliance that has stood unbroken the strain of five hundred years.” A Portuguese force co-operated with British troops from Rhodesia in driving the Germans out of the southern portion of the German colony in East Africa. A division of Portuguese troops was despatched to France to act with the British Expeditionary Force.